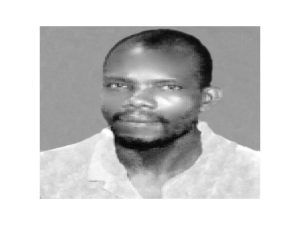

Brother Mohamed Nyei, affectionately called Karmoh, was my guardian angel, protégé, ardent supporter, rule-abiding, and kind. I remember him beating up a boy so severely for hitting me. The police detained him at the local police station downtown Tubmanburg, Bomi County. The next day, Dad and I went to the police station and released him.

Brother Mohamed Nyei, affectionately called Karmoh, was my guardian angel, protégé, ardent supporter, rule-abiding, and kind. I remember him beating up a boy so severely for hitting me. The police detained him at the local police station downtown Tubmanburg, Bomi County. The next day, Dad and I went to the police station and released him.

The last time I saw him was at the Grand Central Gas Station in Tubmanburg. He accompanied me there to say goodbye as I take a passenger car to Monrovia and then to Morocco to pursue postgraduate studies beginning in the fall of 1989, before the Civil War. He was quiet. He didn’t say much to me, nor did I engage him in any conversation. But I felt his love through the way he looked at me. One of the most remarkable things about him was his generous support when I was studying at the University of Liberia. He often traveled from Bomi County and came down to Monrovia to see me and surprise me with a financial contribution.

The bond that units Brother Karmoh and I are more significant than being born of the same parents. He never lied to me. He never bullied or hit me. He never discouraged me from pursuing my dreams. He never cheated me or told a false tale about me. All that I remember about Brother Karmoh was his uncanny devotion and commitment to protecting and supporting me.

Although he was not sportive or belonged to any gym club, Brother Karmoh was virile, athletically built, stalwart, muscular, and handsome. I envy his poise and the great choice of the spouses he married.

When Brother Mohammed K. died, I sent the family a copy of the eulogy I prepared. In that statement, I said: “When Allah intends to enter you into paradise, He will make you upright and kind.” Brother Mohammed Nyei was indeed the son of Alhaji Varmunya Nyei, whose creed was abiding faith in God, be there for the family no matter what, and make our communities and the world a better for all.

I was sad to leave the family, especially, Mother alone entirely in his care. She had chronic knee and arthritis problems. She was wan and losing her independence; she was approaching her twilight years. Brother Foday, who used to take care of her and the family, had gone to the United States five years earlier. Sheikh Nyei was very young at the time, and Brother Samuka was slowly losing strength due to old age.

The family had this tacit agreement to take advantage of any opportunity to pursue overseas education to receive advanced and competitive knowledge and gain lucrative future employment opportunities but must return home to take care of the family. I reneged on that agreement. Brother Karmoh completely fulfilled his part of the bargain of taking care of the family in my long absence and died doing it, for all of us.

There is so much that we have lost, including mothers, brothers, uncles, aunts, and many more. Brother Foday also died on me here in the United States. But the death of Brother Mohammed K. Nyei, up to today date, continues to distraught and sadden me. I least I buried Brother Foday Nyei, sat at his grave, prayed, and manifested the deep sorrow for his sudden departure from this life.

The children of the Brother Karmoh and Foday, affectionately called Moiwai, are going to help me reconstruct the life they know about their dads, and together, we shall remember and celebrate their memories forever.